I den här intervjun med Sandra Ringarp diskuterar vi den föreläsning om HBTQI i terapirummet som hon höll i samband med ISTDP-föreningens årsmöte för ett par månader sedan. Vi pratar även om hennes centrala inspirationskällor som ISTDP-terapeut och hennes nya bana som ISTDP-handledare och -lärare. Sandra Ringarp är leg. psykolog och arbetar vid ISTDP-mottagningen Stockholm som ISTDP-terapeut och -handledare. Hon är knuten till svenska ISTDP-institutet.

Du föreläste nyligen om HBTQI och ISTDP för föreningens medlemmar. Hur kändes det?

Jag var ganska nervös! Men det var väldigt roligt också, att få dela med mig av denna kunskap till vårt ISTDP-community kändes väldigt fint. Responsen var varm och nyfiken och det blev intressanta och fördjupande samtal. Jag har många patienter som söker sig till mig just för att de önskar en terapeut med HBTQI-kunskap, därför kändes det extra roligt att få föreläsa om det här.

Vad var de centrala idéerna som du förde fram och som du tycker är viktiga för ISTDP-terapeuter att känna till?

Det räcker inte att vara öppen och välvilligt inställd i ett vårdmöte med en minoritetsgrupp. Kunskap är en förutsättning för att kunna erbjuda ett tryggt rum. Med kunskap menar jag dels kunskap om vilka de här personerna är – vad står varje bokstav i HBTQI för? Och dels kunskap om hur de här personernas levnadsvillkor ser ut i Sverige. Vad säger forskningen om psykisk ohälsa och erfarenhet av våld och trakasserier i den här gruppen?

Det är också viktigt med kunskap om minoritetsstress vilket den här gruppen och andra minoritetsgrupper är hårt drabbade av. Minoritetsstress uppstår när minoritetsgrupper bryter mot rådande normer i vårt samhälle. Att göra det kan innebära att utsättas för okunskap, kränkningar, våld, hot om våld, trakasserier och något som kallas för mikroaggressioner. Mikroaggressioner är blickar, frågor och kommentarer som speglar okunskap eller fördomar, vilket kan ske mer eller mindre omedvetet. Även välmenande kommentarer kan vara mikroaggressioner – just för att de sätter fingret på att personen avviker från normen. Man blir helt enkelt ständigt påmind om att man avviker från normen. Det här är belastande när det händer, men också förväntan/oron för när det ska hända nästa gång är belastande.

Även om kunskap är viktigt kan vi självklart inte veta allt. Märker jag i ett möte att jag saknar en viss kunskap är jag öppen med det och säger att jag ska läsa på tills nästa möte. Det viktiga då är att vi inte lägger ansvaret på patienten att vara den som utbildar oss.

Är det något annat som är viktigt att tänka på för oss som terapeuter i mötet med minoritetsgrupper?

I mötet med minoritetsgrupper är det också viktigt att vi som terapeuter tar en titt på oss själva. Hur är samhällets normer internaliserade i just mig? Vi har alla normer internaliserade och kan vi bli medvetna om hur de tar sig uttryck inom oss så kan det minska risken att vi till exempel utsätter våra patienter för oavsiktliga mikroaggressioner. Varför vill jag säga den här positiva kommentaren om en persons läggning? Är det för att jag blir lite nervös i mötet? Eller, frågar jag detta för att jag verkligen behöver veta det, eller är jag bara nyfiken? Om svaret är det senare får vi bita oss i tungan, för patientens integritet väger alltid tyngre än vår egen nyfikenhet. Det är viktig att ha med sig att det väcker känslor när människor bryter mot normer. Om vi kan vara förberedda på detta och ta en titt på de känslor som väcks i oss har vi kommit långt.

Det är också viktigt att vara medveten om att många HBTQI-personer har negativa erfarenheter av tidigare vårdmöten, något som såklart kan komma upp på olika sätt även i terapirummet och som vi kan behöva prata om.

Den psykiska ohälsan är väldigt stor bland HBTQI-personer och andra personer som utsätts för olika former av strukturell diskriminering och förtryck. Finns det särskilda interventioner som ISTDP-terapeuter kan behöva lära sig för att arbeta med minoriteter?

Jag tror faktiskt inte det. Att arbeta med minoritetsgrupper handlar inte främst om specifika interventioner, utan om kunskap. Med kunskap har vi förutsättningar för att skapa ett tryggt terapirum – vilket i sin tur är förutsättningen för att vi kan använda oss av alla de goda interventioner vi redan kan.

Många HBTQI-personer söker sig som sagt specifikt till en terapeut med HBTQI-kompetens. Min erfarenhet är dock att det väldigt sällan är för att man vill prata om något kopplat till just sin identitet som HBTQI. Oftast vill man helt enkelt prata om precis det som alla andra vill – relationsproblem, depression, ångest, självkritik och så vidare – men man vill göra det i ett tryggt rum.

Vilka är de vanligaste bristerna i vården i mötet med HBTQI-personer?

De tre vanligaste bristerna är dels heteronormativt bemötande, dvs. att man förutsätter att alla är heterosexuella cispersoner som lever/vill leva i tvåsamhet. Det är också vanligt med kunskapsbrist vilket leder till att personen själv behöver utbilda sin vårdpersonal vilket både blir en stress för patienten och tar upp värdefull tid som patienten behöver till att få hjälp med sina problem. Det kan handla om att man får informera vårdkontakten om vad det innebär att vara en transperson, till exempel.

Det är också vanligt med över- eller underfokusering på sexuell läggning eller könsidentitet, alltså att man som vårdpersonal antingen inte pratar om det alls eller att man lägger för stor vikt vid det.

Ibland stöter vi på patienter vars omständigheter vi inte riktigt förstår. Finns det någon enkel gräns för när man ska hänvisa en HBTQI-person till en kollega snarare än att läsa på och ta sig an ärendet själv?

Jag tänker att det är viktigt att vara ödmjuk och öppen inför att vi inte alltid är rätt person att hjälpa en patient. Samtidigt finns det en risk att vi backar inför det okända, att vi inte vågar när vi egentligen kanske skulle kunna. Jag tror att vi behöver ställa oss två frågor, dels vad vår professionella bedömning är, har vi/kan vi skaffa oss tillräcklig kompetens eller kan vi inte det? Men också frågan ifall det handlar om bristande kompetens eller om osäkerhet inför något vi inte är vana vid? Jag hoppas på att vi blir många fler terapeuter med HBTQI-kompetens, och för att komma dit måste vi också lära oss nya saker och inte backa för det okända och nya.

En annan viktig aspekt tänker jag är att normbrytande per definition väcker känslor och när vi möter människor som bryter mot normen kan det självklart också väcka känslor i oss. Stöter vi på något som vi känslomässigt har svårt att hantera så tror jag att det kan vara bra att backa i den typen av ärenden tills man gett sig själv utrymme att hantera det som väckts, genom att t.ex. skaffa sig mer kunskap och undersöka hur samhällets normer reproduceras i våra egna reaktioner. Annars kan det nog bli onödigt svårt, både för patient och terapeut. Ingen patient ska behöva få sin identitet ifrågasatt i terapirummet, och har vi svårt att stå bakom ett sådant förhållningssätt är det istället bättre att hänvisa vidare.

Om vi pratar lite om dig som terapeut, vad håller du på att lära dig just nu? Brottas du med något särskilt?

I min utveckling som ISTDP-terapeut tycker jag att vissa nya utmaningar dyker upp allteftersom, medan andra följer mig längs vägen. Att hjälpa patienten att hitta sin egen inre drivkraft till förändring så att inte jag blir experten på patientens känsloliv är ett exempel på något som jag fortfarande kan brottas med efter snart tio år av att fördjupa mig inom ISTDP. Utöver det är jag i en spännande process som terapeut där min nya roll som utbildare och handledare i ISTDP gör att jag lär mig att titta på mig själv och mitt eget arbete på ett nytt sätt, utifrån hur jag lär mig att handleda och lära ut till andra. Att lära ut grunderna i ISTDP gör att jag själv blir påmind om alla små detaljer och skeenden, som kan vara lätta att missa men som är så viktiga för utfallet. Så man kan säga att jag lär mig ISTDP från grunden en gång till just nu!

Du ska hålla några ISTDP-utbildningar under året, är det någon särskild vinkel på ISTDP som du kommer lära ut? Vad har varit dina centrala inspirationskällor?

Jag har inspirerats och inspireras ständigt av kollegor, handledare och utbildare, och där är namnen många. Men jag tror att min största inspiration är arbetet i sig. Min första förälskelse i ISTDP kom ur en desperation när jag arbetade på en vuxenpsykiatrisk mottagning som ny psykolog. Hur skulle jag kunna hjälpa de patienter som hade så hög ångest att det var svårt att ens sitta i rummet med mig? Att plötsligt få ett språk och konkreta terapeutiska interventioner för att hantera detta var stort och gav mersmak. Att kunna hjälpa människor ur det lidande de hamnat i och in i något nytt är något som inspirerar mig ständigt i min kliniska vardag. När det händer kan det vara som att en helt ny värld öppnar sig – kan livet se ut så här! Jag slutar heller aldrig förundras över hur överraskad jag kan bli i mötet med en patient. Det är fint att få vara förundrad och fascinerad av människan framför mig. Och det är inspirerande att se det som redan finns i varje människa, gömt under alla lager. Att det inte är något som behöver skapas, det finns redan där och vi gör tillsammans ett arbete för att det ska få komma fram. Vägen dit kan vara lång och krokig men om vi kan komma dit är det stort att få vara med om. Det är otroligt inspirerande!

Jag ser fram emot att få lära ut ISTDP på ett tydligt och lättillgängligt sätt. Det som jag själv uppskattar med ISTDP, att det är en terapimetod med konkreta terapeutiska interventioner som samtidigt ger ett stort utrymme för att hitta sin egen personliga terapeutstil, det vill jag också lära ut. Och så vill jag att vi ska ha roligt! Att inlärningsprocessen ska få vara nyfiken och kreativ. Den empati som vi har med våra patienter behöver vi ha med oss själva också, inte minst när vi lär oss något nytt.

Om vi tittar på ISTDP ur ett bredare perspektiv, har du någon vision för var vi befinner oss med ISTDP i Sverige om fem-tio år, om du får drömma lite?

Jag hoppas på en bredd i ISTDP Sverige på alla nivåer – föreläsare, utbildare, handledare och terapeuter – och ur alla perspektiv – kön och hudfärg till exempel.

Förutom det önskar jag att vi kan se flera svenska studier på utfall av ISTDP, det är viktigt för etableringen av metoden. Och såklart hoppas jag att intresset för ISTDP kommer att fortsätta att växa, att fler terapeuter får möjlighet att arbeta med denna kreativa och givande behandlingsmetod och framförallt att fler patienter kan få tillgång till ISTDP. Med en bredd i behandlingsutbudet har vi större möjlighet att kunna hjälpa fler, och jag hoppas att ISTDP ska ha en given plats ett brett utbud.

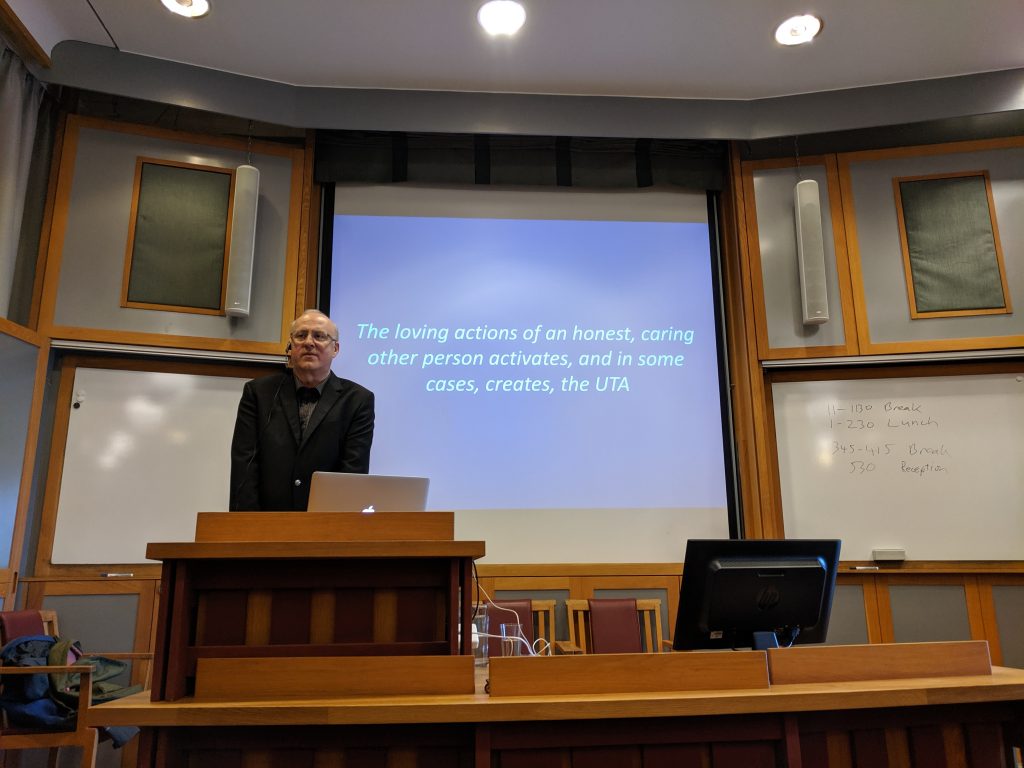

Här kan du se föreläsningen om HBTQI i terapirummet som Sandra Ringarp höll i samband med ISTDP-föreningens årsmöte:

Om du gillade den här intervjun med Sandra Ringarp så kanske du även är intresserad av några av våra andra intervjuer. Här hittar du några av de senaste intervjuerna som vi publicerat:

- Niklas Rasmussen: “Det är så lätt att tappa bort sig själv i ISTDP”

- Maury Joseph: “How much does our theory shape the patient’s experience?”

- Ola Berge: “ISTDP erbjuder ett perspektiv som saknas i psykiatrin”

- Johannes Kieding: “ISTDP is uniquely vulnerable to misalliances”

- Jonathan Entis: “Defiance is the single most important defense”

- Ange Cooper: “I am my patient, they are me”

- Mikkel Reher-Langberg: “Vi använder Davanloos ord, men musiken är annorlunda.”