The limitations of ISTDP. Part 1: Jon Frederickson

What are the limitations of ISTDP? What would a balanced view of ISTDP be like? Just as any approach to psychotherapy, ISTDP is subject to both idealization and devaluation. Over the past few years, we at ISTDPsweden.se have published quite a lot of positive stories and news about ISTDP. Now it’s time to do some balancing. We sat down with some prominent ISTDP clinicians to discuss the shortcomings and downsides of ISTDP. Here's the first part, an interview with Jon Frederickson.

On SUITABILITY FOR ISTDP

As we've talked about before, ISTDP is not a panacea. Which type of problems and patients are not suitable for ISTDP?

Jon Frederickson: Nothing is a panacea in the field of mental health. Types of problems not suitable for ISTDP would include the treatment of traumatic brain injury, neurocognitive deficits, and genuine autism spectrum disorders (not including those mistakenly diagnosed).

Generally, we should offer supportive and not exploratory psychotherapy to patients currently abusing drugs until we have built the affect tolerance that would make exploratory therapy possible. Likewise, some psychotic patients in a severe regression and severely depressed patients may require medication and supportive psychotherapy before a trial of exploratory therapy should be attempted.

ON LEARNING ISTDP

Just how difficult is ISTDP to learn? As far as I’ve heard, no one ever graduated from Davanloo’s training. Should learning ISTDP be easier?

Jon: It’s not just a matter of ISTDP being hard to learn. Learning to be a really good therapist is hard. That is why it is relatively rare. Twenty percent of therapists get eighty percent of the good results. And that is true within each model of therapy. It is really hard to become a highly effective therapist in any model of therapy. You may be under the illusion that you’ve “learned” the model, but the outcome research shows that there is no relationship between our perception of our ability and our actual effectiveness.

Should learning this be easier? Should learning to be a professional musician be easier? Should learning to be a chess master be easier? No.

It should be hard because it is hard. That is reality. However, in the case of psychotherapy: should our teaching be better? Yes.

Research shows that graduate training has no effect on therapist outcome. What a disaster! Should our supervision be better? Yes, because research shows that 93% of therapy supervision is inadequate and 35% harmful.

At least in music and chess, it is clear what skills need to be learned and there are materials which train students in those skills. We have no agreement on the fundamental skills necessary for effective practice in psychotherapy and no materials for training in those skills. So, in response to your question, yes and no. Learning a complex skill like psychotherapy should be just as hard as becoming a violinist.

Yet, it is currently way too difficult to achieve this skill level as therapists because of the poor quality of supervision generally available. As well as the inadequate, indeed, useless quality of graduate training. The useless seminars offered which do not show effective treatment, and the failure to use videotapes to develop an empirically validatable model of teaching and supervision.

In case you wonder if I am outraged by this state of affairs, you read me accurately.

ON JARGON

Unlocking the unconscious is sometimes described as a unique aspect of ISTDP. But other models also facilitate emotional breakthroughs and spontaneous reporting of previously repressed material. Could the jargon mystify the therapy process and put ISTDP at risk of distancing from other models?

Jon: Obviously, any emotionally transformative human experience involves a breakthrough to feelings that were previously out of awareness. It even happens at movies! One danger in any model occurs when we use jargon to “professionalize” our field and to create a sense of mystique such that outsiders “could not possibly understand” what goes on behind closed doors.

Jargon creates another danger: we might accept a piece of jargon, usually a description, and mistake it for an explanation. As a result, steps in logic are skipped, and flaws in an argument remain invisible. In case you wonder what I mean, here are some common vague terms which are ill defined and have come to mean everything: mindfulness, awareness, and superego. Here is a term which doesn’t mean what it claims: diagnosis. In fact, what we call diagnoses are merely a description of symptoms, not a diagnosis of their cause.

Do you think there's a need for a conceptual “makeover” in ISTDP to facilitate dialogue with other models?

Jon: I don’t think ISTDP needs a makeover as you suggest. I think all therapists in all models need to abandon vague concepts, acronyms, and made up words for plain English, or whatever your native language is. If you cannot explain what you are doing so it could be understood by an adolescent, either your language is a barrier, or you do not fully understand what you are trying to say.

We work with humans, speaking a human language of the heart. Any theory we describe should be able to be put in these terms. If we dropped jargon, we could even talk to other clinicians. As it is, today much clinical dialogue at conferences becomes useless because the exchange of abstractions takes the place of examining the actual data. And the narcissistic display of mysterious language becomes a way to avoid the humbling act of revealing one’s actual work.

ON SUPERSHRINKS AND RESEARCH GAPS

Even though there’s more and more research showing the efficacy of ISTDP as a whole, there’s still not so much high-quality research on the different ingredients of the therapy. A notable contribution is the recent Iranian study showing that ISTDP without challenge was just as effective as standard ISTDP. Given the lack of studies, ISTDP is largely an “oral tradition” where the experience of specific prominent therapists (be that Davanloo or yourself, for example) is very influential. What are some of the challenges with the specific ingredients of ISTDP?

Jon: The Iranian study was important, but like all studies, it's easy to forget the context. In fact, challenge is appropriate only with about 25-30% of patients, the ones who primarily regulate feelings with isolation of affect. Challenge is not appropriate for the other seventy percent of patients who are in repression and fragility. So it should be no surprise that ISTDP without challenge would be effective, because that is the effective form of ISTDP for 70% of patients!

When students try something I suggest, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Why? Sometimes they aren’t doing what I suggest. Sometimes I was wrong; I misread the patient, and the patient’s response gives a clearer idea of how to proceed. Sometimes, the therapist is initially helpful without realizing it, but is unable to understand and categorize the patient’s subsequent responses. I don’t think the issue is the individual clinician per se, although the effect of the therapist is powerful. I see repeatedly that there are certain patterns of response across patients and across cultures. When we address these patterns – feelings, anxiety, defenses, and transference resistance – we find patterns of response to intervention.

Now we get to the interesting question: the relationship between principles and rules. For instance, when a patient is struggling to bear mixed feelings, the principle is to help the patient bear mixed feelings without anxiety shifting out of the striated muscles. Sometimes, to make things simple, people make up a rule: “Thou shalt pressure to feelings in this way. Repeat after me!” The student, alas, learns to become a clone who follows rules rather than a person who operates according to principles. There are many interventions that could embody the principle of building affect tolerance. And those interventions could be in response to specific words or dynamics the patient has used. They could arise from the therapist’s experience, feelings, and intuition. They could arise from their mutual co-created responsiveness.

In music, the voice leading (how voices related to each other, for instance, in a fugue) was not supposed to have parallel fifths. That was a rule. Suddenly Debussy comes along and he uses all kinds of parallel voice leading to create effects of great beauty. What had been a rule was revealed to be subject to a higher principle. Thus, it could be broken.

Alas, the early phase of ISTDP training often involved people following rules without understanding the overarching principles, to which those rules are subject. If we ritualistically follow rules, therapy is very easy to learn, though robotic. If we follow principles, then we understand the purpose of our interventions, and that allows for creativity in the therapist and responsiveness to the patient.

Good therapy is like jazz. A jazz musician knows the key, the melody, the harmonies, the underlying principles and he improvises based on that underlying structure. He appears to be breaking rules, yet he is guided by underlying principles. A good teacher orients you to principles whether he is teaching you chess, music, or therapy.

ON IDEALIZATION AND DEVALUATION

Historically, the ISTDP community has unfortunately been subject to sect-like behavior such as a strong idealization of charismatic figures (such as Davanloo) along with exclusion and devaluation of critical voices. Is there something in particular that makes ISTDP vulnerable to this? What can we do to safeguard against this in the present and future?

Jon: As we know from the work of Bion and other group theorists, when humans form groups, groups become irrational.

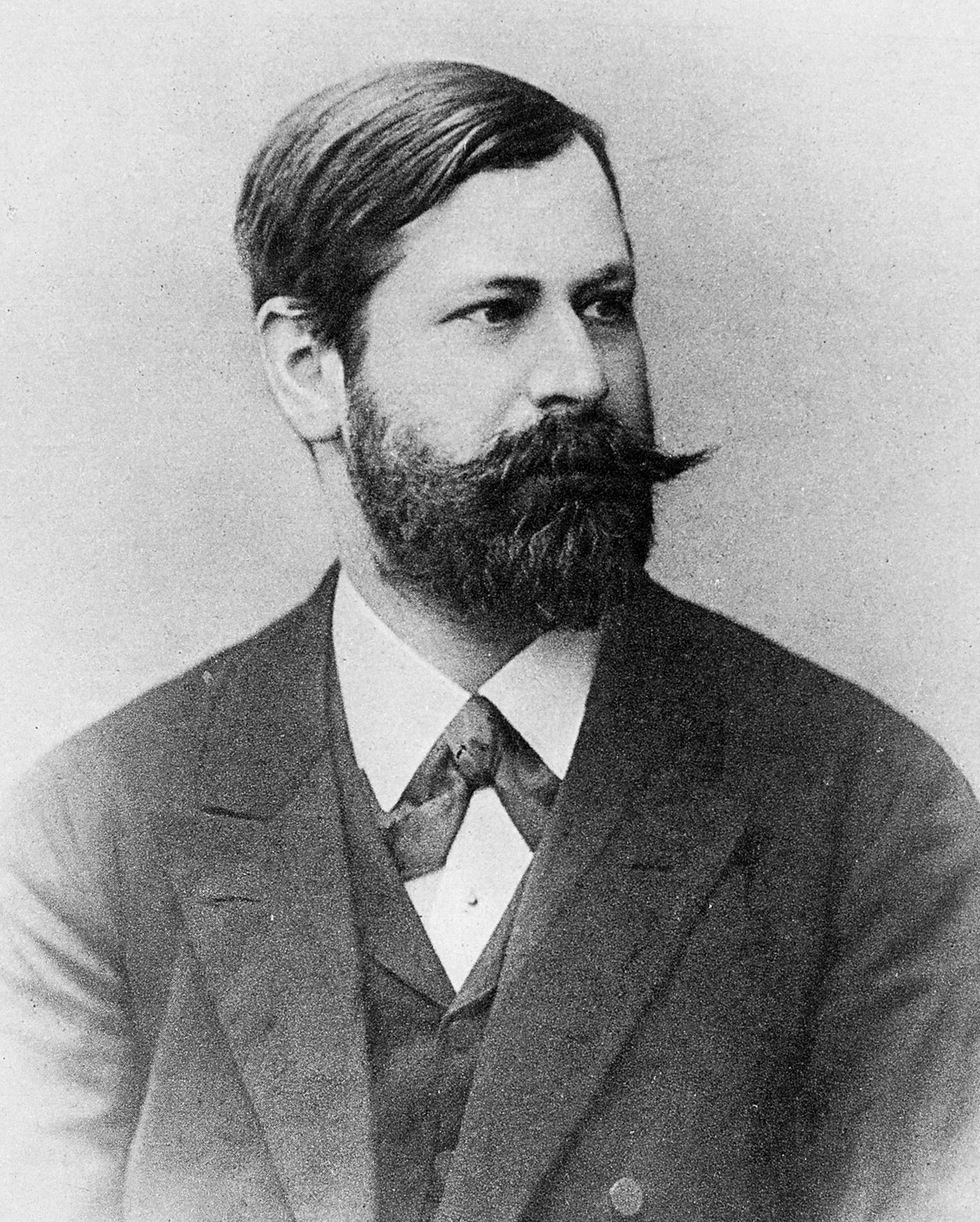

Friedrich Nietzche said that earth is the insane asylum of the universe. Every day we see plenty of evidence for this. Idealization of teachers happens in all models to greater and lesser degrees. Think of Freud, Klein, Davanloo, Rogers, or Beck. Every one of them has been idealized, and each of them has been devalued.

There will always be some people who want to idealize their leader and devalue the rest. We have to understand this as not a problem of a given model, but a problem of the human condition. To avoid the anxiety that our knowledge is partial, our theory will be changed and surpassed is the way of all scientific knowledge, and that whatever we create today will be forgotten in the mists of time, we seek magic.

We idealize a model and view it as the final, complete answer. We idealize some figure. Then we devalue other models and teachers. Then we imagine we are part of some secret society of superior therapists in contrast to all those “others.” This pattern has been described in cults, and, sadly, this kind of cult formation is common in the therapy field. All we can do is make ourselves aware of this temptation to idealize and devalue.

And we can also step back and realize what makes us anxious: 1) our knowledge is always partial; 2) we will never have all the answers; 3) we will always be flawed and fail with some people; 4) we will never have the final, complete understanding of the human condition in our lifetime; and 5) whatever we achieve, whatever we build is transient and will disappear. This is reality.

When we cannot bear this death anxiety, we engage in the denial of death through the magical claim that we have found the eternal answer, the eternal group, and the theory that has somehow transcended time. Due to death anxiety, this pattern will probably always recur in humanity, including groups of therapists.

OTHER LIMITATIONS AND WEAKNESSES

Do you see other major limitations or weaknesses in ISTDP?

Jon: My major concern here does not have to do with ISTDP but with the psychotherapy field as a whole. Our understandings all too often are not linked to other areas of knowledge such as sociology, group theory, family studies, and economics. These different fields appear as silos. Take for instance the study of patients who suffer from borderline personality structure or psychotic patients. There is so much good research on the relationship between their psychological difficulties and predictable patterns of family dysfunction.

Yet this research keeps getting forgotten, only to be done again by the next generation. These patients are often examined only from the individual perspective, and we forget the family system that generates these patterns. We look at psychological issues, yet we seem to have forgotten the role of social class and capitalism in character development. Fromm wrote much on that, yet today in the US it is a taboo to recognize the role of class.

Or look at racism in the US or the caste system in India as examples of the transgenerational transmission of trauma. And then there is the tendency to underestimate the role of neurocognitive deficits and brain injury in borderline and psychotic patients. The psychotherapy field has become so focused on the individual, that we easily lose sight of the group and family context, the class context, and the biological context. Then we end up with these different research silos: each reducing the patient to one of these categories, when we need to open up to the interrelationships between them.

Do you find there are aspects of ISTDP that we have to address and change in order for the method to thrive?

Jon: It depends on how you define ISTDP. Some describe it as the method. If so, that is ritualism, and, yes, that should be changed. Some describe it as what some teachers do. If so, that is idol worship, and that should be changed. For some, it is a set of rules, and that should be changed.

For me, ISTDP is a set of meta-theoretical principles which allow us to integrate any of a number of techniques. The most important principle is to assess each patient response to intervention to find out if you met the patient’s need in the moment. And these principles are based on a psychoanalytic theory of childhood development and attachment theory. The techniques of cognitive-behavioral therapy, somatic experiencing, gestalt therapy, or internal family systems, you name it, can be incorporated because the key issue, no matter what technique you use in the moment, is: am I meeting the patient’s need in this moment as revealed in her last response to intervention?

In this sense, I am suggesting that we need to move beyond the idea of a model toward an integrative way of thinking and responding. Models can only point toward that. Replication of models does not lead to good outcome. We have to foster a kind of integrative emotional feeling and responsiveness in our work that models and theories can only point toward.

The best therapists in each model look surprisingly alike according to research. This suggests to me that the key factor is not just their model, but a quality of thinking, feeling, responsiveness, and self-reflectiveness that is filtered through their model.

It’s like driving. It doesn’t matter what kind of car we see. It’s the nut behind the wheel.

Jon Frederickson's latest book Co-Creating Safety: Healing the Fragile Patient came out a couple of weeks ago.

If you liked this article, you might find our other material interesting. Following this link you can find more material in english. Below you’ll find a list of our recent interviews.

Medlemsdiskussion