Johannes Kieding: "ISTDP is uniquely vulnerable to misalliances"

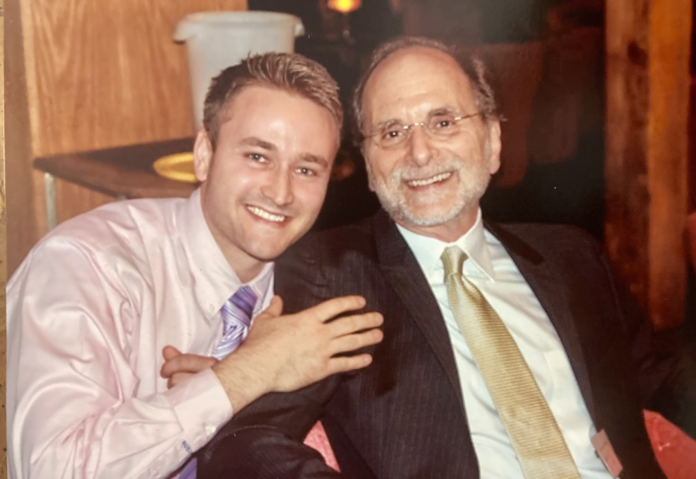

In September, we have the great pleasure of welcoming Johannes Kieding to the ISTDP Academy, where he's presenting on the theme of defiance. Johannes is a LCSW in private practice in Tuscon, Arizona. He was trained by Marvin Skorman and runs a much appreciated Youtube channel where he puts out educational material for ISTDP and ISTDP-informed therapists. He's also the administrator of a large facebook community for ISTDP therapists, "ISTDP Peer Community". We have previously published a text by him outlining some of his main ideas. In this interview we discuss alliance-ruptures, relational ISTDP, defiance, systems of resistance, challenges to learning ISTDP and a few other things.

What do you feel inside right now?

Excited and ready for a day to see my wonderful clients and supervisees. This career is a dream come true.

You've worked with Marvin Skorman for many years, and last year we published one of your texts about your take-aways from working with him. Marvin is now retired. How is work without Marvin coming along? Are you noticing changes?

Indeed indeed. Initially it was a bit rough on me, but it’s also good to really find my own feet and experience my independence. Few people on this planet have influenced me like Marvin, so in a way I feel that I carry part of his signature in me, but it has molded itself into my own style. When I am with patients I am hearing more and more things come out of my mouth that I don’t know where they came from. So I seem to be finding my own way of doing things.

To me you represent a strong voice in the ISTDP community for the "real relationship" approach to ISTDP. Relational ISTDP if you will. Why do you think you came to approach ISTDP in this way?

Before I answer how I came to it, I want to define our terms. What you think of as relational may not be what I have in mind. By ‘relational’ I mean I am trying to work with, not ‘on’ the patient. This means I am not laying a trip on the patient, not engaging my schtick, not just applying a technique.

Instead I try to understand the patient on their terms, to look at things through their eyes and seek their feedback that I have understood their first person perspective. This is a big part of what dynamic exploration and inquiry is about — really getting to know the patient and the themes in their lives that relate to their chief complaints and to their strengths that I will want to capitalize on during the work.

This part of the work is about developing a shared language together, short-hand references that may be totally unique to the particular patient. Though I attend to latent content, I do not ignore the manifest content, I do not ignore what the patient is actually saying. When I offer alternative or new perspectives, I check in to see if what I am saying tracks for them, if they agree or disagree.

I try to hone in on the patient’s will, their priorities, and go out of my way to ensure that I am not pushing my own agenda on the patient. So when I ask if they want to take an honest look at their feelings, I monitor the response to make sure the patient is really behind their “yes.” I try to ensure that I have a real collaborator and continuously stress the client’s autonomy and right to choose.

To me this overall seems like standard ISTDP principles. But what do you think stands out in your approach?

Through the prism of what I think will further the patient’s goals, I may include some of my subjective responses to the patient. If I am asking the patient to be totally open, I don’t think it makes sense for me to be reticent about being self-revealing when that seems to be what the patient needs. Certainly not self-revealing for its own sake, but when the patient seems to need that.

Even if I am working vertically, if the aforementioned ingredients have been established it’s a working with, not working on, even though at that stage I am blocking every single patient response until we get the unlocking — this can certainly look like I am working on, not with. But the key is whether or not I've built a foundation where the patient and I are truly on the same side, pulling in the same direction, both going after the resistance.

As for the question of why I came to stress this approach to ISTDP: one reason is that when I was not working relationally, I had a lot more misalliances. I had patients walk out of my office sometimes. I had clients who had repeated unlockings but still were not getting better. So I came to the conclusion that in order for unlockings to be truly healing, they have to occur within a context of a really trusting relationship. A secure attachment, if you will.

If I am just applying techniques like a technician, I may get lucky and help the client have some unlockings, but this didn’t seem that helpful.

Think of sex: you can mechanically produce an orgasm through skilled technical maneuvering, but this kind of orgasm is quite empty. The orgasm that comes from making love, where you are truly connecting with your whole being, is far richer and more meaningful. This is the difference between unlockings that come from merely applying techniques and unlockings that come after more relationship building and more clarity for the patient.

I think the other reason is that my teacher and mentor, Marvin, was steering me in this direction based on his prior mistakes and experiences where his rigidity created less than optimal therapeutic outcomes. So I got it both from my own experiences with clients and from my mentor.

Earlier this year you did a few presentations on repairing alliance ruptures. How come you emphasize this in your work? Do you think alliance ruptures are more common in ISTDP than in other schools of therapy?

Hopefully my previous response gives you an idea of my response to this question. Based on my own experience, Marvin's experience, and countless cases where trainees present their work to me, I do indeed believe that ISTDP is uniquely vulnerable to misalliances.

This is greatly mitigated the better we become, the more we attend to the unique themes related to the patent’s difficulties, the less invested we become in a specific outcome, and the more we emphasize the conscious alliance, which of course includes clear, non-compliant agreements around problem and task.

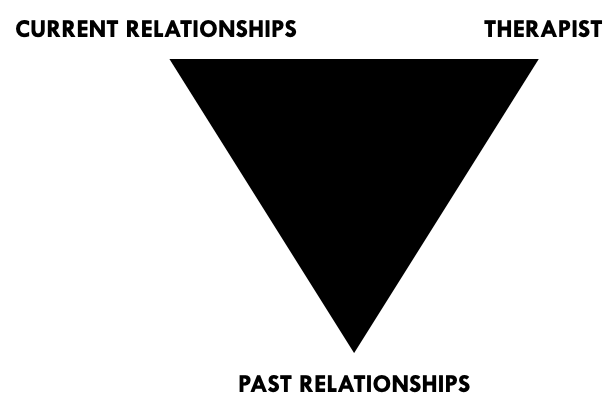

When I saw Davanloo’s work (especially from the 1980s and before), and when I read his transcripts, more often than not I see him being incredibly attuned to the patient. Truly meeting them where they are, then bringing the patient along with him so that they can truly see why they may want to face what they have been avoiding.

Somehow when many of us try to do something akin to Davanloo, in our eagerness to have a breakthrough or unlocking we miss this part that has to do with really meeting the patient where they are, and step-by-step bringing the patient along with us to ensure real buy-in and conscious understanding of the therapeutic task. I can’t tell you how many times I have seen trainees try to drag a patient through the central dynamic sequence, without having a real collaborator. That is what I refer to as laying a trip on the patient. It’s exhausting for the therapist and typically not very therapeutic for the patient.

I’ll never forget this one supervision session from some years ago where the trainee showed a case and where the patient was very forthcoming, collaborative and open, but because the trainee saw some tension and a moment where the patient looked away, the trainee labeled this rather undefended patient “highly resistant,” and thought it proper to begin repeated pressures to feeling. The patient was quite undefended actually.

This suggests to me that there is an element in how people are being trained where the ratio of interpretation to experience is too high and too theory forward. For an accurate psychodiagnostic picture, there needs to be sufficient pressure, but accurately targeted to the front of the system. I see people decide on a psychodiagnostic category based on far too little data.

Davanloo’s diagnostic roadmap is an interactive one — I may have a patient in front of me aimlessly rambling, but this doesn’t tell me anything in and of itself. I need to bring this to the patient’s attention and see how they respond. The patient may bounce back and readily get back on track and focus again, or they may evade the issue.

Only by carefully monitoring the patient’s responses when I identify the main barrier to progress do we have meaningful psychodiagnostic information. I see people just look at an initial presentation, or patient responses to the therapist intervening but the intervention does not address the main progress-preventing behavior, and then come to diagnostic conclusions without availing themselves of sufficient data.

Here's another example. A trainee labels the defense of diversification and changing the topic, but because of insufficient dynamic exploration, they are not linking these defenses into the larger themes. The patient may be changing the topic because they are pulling for a supportive relationship where they just want to be heard and have a fire-place chat, and are therefore trying to get away from goal focused work. If we are too narrowly focused we just see the most pronounced aspect of the defense (changing the topic and diversifying). But if we zoom out and attend to the larger themes, we might see that the defense of changing the subject ties into a life-long pattern where the patient is constantly looking for comfort and self-soothing. ‘Self-soothing mode’ would in this case be the actual major column of defense, but we don’t see that if we are not able to zoom out and get the bigger picture, the bigger themes that the individual defenses are rooted in.

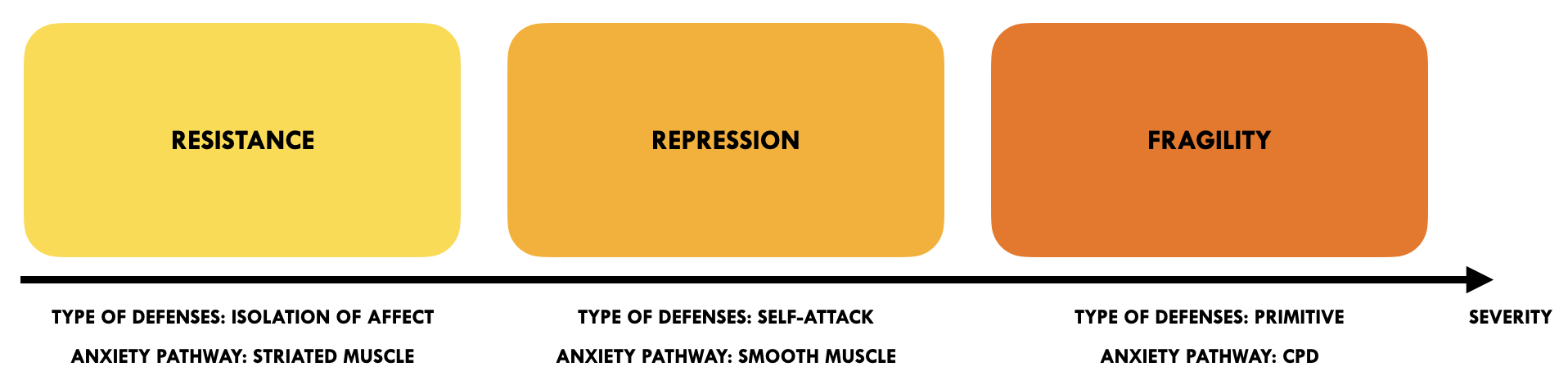

Over the last year we've had a few discussions on the problems with the conceptualization of fragility. I sustain the value of the "systems of resistance" approach suggested by Jon Frederickson, where we have three distinct diagnostic categories (resistance, repression, fragility) that each need different treatment approaches. And you, on the other hand, have come to stress the underlying similarities behind these difficulties, arguing that the dividing of these categories might introduce more conceptual complexity than needed. Can you say something about where you stand regarding this right now?

I am for whatever helps the patient, so if using this theoretical construct helps, I am for that.

I do not see resistance as a stable trait. The person of the therapist, the therapist’s approach, the particular zone in the unconscious that is being approached, the nature of what the patient is resisting, the strength of the stimulus that is evoking feelings, the particular juncture of the treatment — all of this impacts the picture of resistance.

And again, in the spirit of being clear on what we mean by our terms: I have heard resistance being defined by how a patient avoids (eg. high resistance being defined by resistance to emotional closeness), and I have heard resistance defined in terms of level of collaboration and openness (eg. is this patient willing to work hard and be open about what's going on inside?). I tend to find the latter understanding more helpful.

The issue I have taken with the implication of the theoretical model you refer to (at least as you described it to me) is the notion that a fragile patient is somehow less defended than a patient with higher ego-adaptive capacity. Surely a fragile client will not have access to a certain class of defenses, but defending against feelings and real contact through distortions (splitting and projecting) is just another way of defending. In other words, regressive defenses still amount to ways of defending and distancing from undistorted feelings and undistorted three-dimensional others.

The most helpful and accurate way of defining the level or degree of resistance that I have heard comes down to how invested a patient is in defending their own defenses once these defenses are pointed out. If memory serves, I first heard of this conceptualization from Patricia Coughlin.

The client’s capacity will determine what kind of defenses the patient will have in their arsenal, but I disagree with the idea that a fragile client is somehow by default less defended. Less access to higher order defenses, certainly, but regressive defenses still constitute forms of resistance.

Though it’s important to be clear with our metapsychology and have a firm grasp on the principles that guide our work, at the end of the day I think that being overly focused on these conceptual frameworks can detract from the work.

My heart is in the trenches where it’s about the patient in front of me, the trainee in front of me, and I do not always find these sort of theoretical constructs helpful when it comes down to it, when it comes down to where the rubber hits the road. But if others do, that is fine by me.

The ‘systems of resistance’ lens can be very useful. I have it in the back of my mind and sometimes it comes in handy. But generally I rely more on the model that breaks down formal defenses into either repressive or regressive, and then also looks at tactical defenses — where the tactical defenses are either free-floating or tied into a major resistance. But really, as long as we do not allow our theoretical maps to get in the way of connecting with the patient, I am for whatever gets the job done.

Related to the above question, do you think there is one ISTDP or many ISTDPs? And do you think ISTDP should be further developed or is it at this point more important that we try and comprehend what Davanloo was offering?

I am having a hard time connecting to this question. Davanloo spent his life developing this incredible way of working, and since none of us are a carbon copy of Davanloo (and few even in good standing with Davanloo), everyone is doing some adaptation of what they learned from Davanloo or Davanloo’s students.

As long as we acknowledge that we are engaging in some form of adaptation of Davanloo’s work and that none of us are some final authority on his work, I think we are above board. Spending time thinking about who is and who is not doing ISTDP does not seem like time well spent, to my mind.

We are all engaged in some adaptation, as far as I am concerned. I encourage people to bring their own personality into their work and to do what works. If that looks like classic ISTDP, great, and if not, also great. Pointless turf wars about who is the real deal and who is not do not appeal to me.

You work hard to make ISTDP available to a broader audience through your youtube channel. What's driving that?

I think I offer something unique and feel strongly about making that available to those that are interested.

What are you struggling with right now as a therapist? What's your learning edge?

With highly resistant patients, when it’s time to ramp up with peppered pressures and challenges, it’s important to be very precise about the major column of defense and to not allow much time between the interventions and to not allow the patient to interrupt the process with their defenses, so my growth edge at the moment is to be more crisp and firm and really hit the major column with the right pressures and challenges in a way that blocks every single patient response short of an unlocking. That’s where I could improve a bit.

In September at the ISTDP Academy you'll be speaking on the theme of defiance. Why this topic? What can we look forward to in the presentation?

Defiance, and its flip-side — compliance — is a universally common defense, and it can be difficult to work with. You will see how I work with deep-seated defiance that is more or less conscious, and you will see how much I stress undoing the omnipotent transference resistance, which involves not doing more than my part and not watering down the head-on collisions.

You will see a different way of “reaching for the patient” that ensures that I do not give the patient anything to defy. You will see a kind of inverted pressure.

I will also show the working through phase, and parts of the termination session, to really demonstrate what character change looks like.

Where do you see ISTDP going in 5-10 years? Where do you want it to go?

I hope that it will be more widely accessible to a larger swath of therapists, and that those who rely on other methods can still make use of some of the principles of ISTDP.

I imagine that there will always be the true believers and I hope that these people will engage the model in a way that includes their humanity and the ingredients I referred to when I spoke of the relational approach to ISTDP, and that there will be room for the ISTDP-informed therapist who enhance their work through aspects of ISTDP, short of the kind of immersion of the true believer.

Over the years, we've done a number of interviews with ISTDP therapists and teachers here at ISTDP-sweden. Here are the latest ones:

Medlemsdiskussion